An Overview of Okinawan Kobudo

Filed under: Admired Martial Artists Month, Guest Post, Tales from the dojo

BY: C. BRUCE HEILMAN

Today most people involved in the martial arts and even many of the general public have become aware of some of the martial arts weapons. Probably, the most widely known of the Okinawan weapons is the Nunchaku, which received its notoriety in numerous martial arts movies during the 1970’s and 80’s. Others may to a lesser extent be aware of the Bo, Tunfa and Sai. However, there exist a number of other significant weapons to traditional Okinawan Kobudo that the knowledge of which is limited to the most serious Karate/Kobudo practitioners.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT

The study of ancient martial arts weapons, and their related techniques, has over the centuries resulted in the development of a variety of schools and systems. These systems can be divided into two basic groups purely for combative purposes: 1) Bugei – martial arts, and 2) Budo – martial arts. The Budo form was developed from the Bugei and Jitsu forms. The Okinawans call these forms "KOBUDO", or ancient weapons arts.

Around 400 years ago, Japan began to assert control over the Island of Okinawa. One of the edicts forced the Okinawan people to turn over their weapons to the Japanese. The move was made by Imperial Japanese leaders with almost no realistic political foresight and very little insight or perception into the Okinawan way of thinking. The ruling classes assumed that to gain political and financial control over this tenacious island race, all that was necessary was to disarm the people. The edict specifically ordered that "all weapons" be turned over to the authorities. Little did the authorities realize that the Okinawan people were such a nationalistic race and so strongly devoted to freedom that they would go to any lengths to deceive and/or hide the weapons they needed to fight their oppressors. Thus, weapons were called "farm implements", but underground the fighting population was training in the use and proficiency of these tools. Soon the weapons masters became a most feared force in the battle for political freedom, feared by the Japanese and idolized by the Okinawan people whose protectorate they were.

Today, much of the Island of Okinawa has undergone its own industrial revolution, and most of these crude farm implements have been replaced by mechanical and power tools. Yet, the history of these weapons is still part of the rich traditional background of Okinawan Martial Arts, and as important physical aspect of the arts.

Kobudo practitioners today, as did their ancient predecessors, perfect weapons techniques by training with kata specifically designed to teach and perfect directional movements, transitional movements, body alignment, balance, grace and coordination between body and weapon.

The practice of Okinawan Kobudo, although not formally part of Karate, is almost inseparable from an historical viewpoint. Okinawan Karate practitioners are generally involved to some extent in the practice of Kobudo. While most are at least proficient with a few weapons, few if any can use a wide range of weapons with a high level of proficiency.

The major difference between Karate and Kobudo practice has been that historically, Kobudo practice has not been as systematized as with Karate. Kobudo practice has tended to be focused upon separate "Kobudo Associations". The very existence of these Kobudo associations has however, over time started a trend towards systematization of the Kobudo training, techniques and katas. Examples of such Kobudo Associations include: Shinpo Matayoshi’s Zen Okinawa Kobudo Renmei ; the late Eicho Akamine’s Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinko Kai ; Seikichi Uehara’s Motobu-ryu Kobujitsu Kyokai ; and Motokatsu Inque’s Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinko Kai.

Also, the within the last twenty years we have seen the emergence of combined Karate-Kobudo organizations which have furthered the trend toward systematization of the Kobudo training. One of the earliest was Seikichi Odo’s Okinawa Kenpo Karate-Kobudo Renmei. Other such combined organizations include: Kenko Nakaima’s Ryuei-ryu Karatedo Kobudo Hozon Kai ; Seitoku Higa’s Zen Okinawa Karate Kobudo Rengo Kai ; Choboku Takamine’s Kokusai Karate Kobudo Tenmei ; Ryusho Sakagami’s Itosu Kai, Nihon Karatedo Kanto – Hanbuncho of Hozon Shinko Kai ; Tsueneyosho Ogura’s International Karate and Kobudo Propagation ; and Masafumi Suzuki’s All Japan Budo Federation.

WEAPONS OF OKINAWAN KOBUDO

The major traditional weapons of Okinawan Kobudo include the following:

- Bo

- Sai

- Tunfa

- Kusarigama

- Kama

- Nunchaku

- Eiku

- Jo

- Nunte Sai

- Nunte Bo

- Yari Bo

- Tanbo

- Tekkos

- Tinbe

- Rochin

- Kuwa

A brief introduction to each of these weapons of Okinawan Kobudo is presented in the following discussion.

Bo:

The Bo is one of the most popular weapons of Okinawan Kobudo. In the hands of Masters such as Seikichi Uehara, Shinpo Matayoshi and Seikichi Odo, it was almost an unbeatable weapon due to its reach and striking power. Formally called the "Rokushakubo", where "roko" means six, "shaku" is a unit of measurement of about a foot in length, and "bo" means staff.

As an art form, Kobudo is closely tied to Karate, adopting from the Chinese the basic principles but developing its own Okinawan characteristics. The first of these is the matter of the design of the weapon. The Okinawan Bo is tapered at both ends to provide a more centralized focus for striking the opponent’s body.

The use of the Bo relies heavily upon a good knowledge of karate basics. The Bo operates best from outside the opponent’s weapons swing zone, and it gives its user a strong advantage over an opponent’s shorter weapon. When used at a close range, within the opponents swing zone, the Bo provides a variety of blocking and parrying techniques, but loses some of its distance advantage.

Bo training requires the student to make a lengthy study of the fundamental grips, stances, movements and techniques of striking, blocking, poking, thrusting and disarming. It must be noted that to effectively be able to utilize the Bo to its maximum, the student must be able to use the full range of the weapon.

Sai:

The Sai is a uniquely designed short metal weapon with a long history. Found in India, China, Indo-China, Malaya and Indonesia, its presence in Okinawa probably derives from migration from one or more of these sources. Prototype designs may be seen in the Trident-shaped weapons of ancient times. The ancient Indonesian civilizations on Sumatra and Java, which had contact with Okinawa used the weapons in their fighting arts.

The Sai is primarily a defensive weapon and is effective against an enemy armed with blade, staff or stick. The length of the Sai varies with the most popular lengths between 15-20 inches. It was generally made from iron or steel and weighed between one to three pounds. The Sai is generally used as a truncheon, although its earlier forms derived from a bladed weapon. The Sai may be used to deflect, block, or parry a cutting or thrusting attack of a bladed or staff weapon.

The Sai were usually carried, one in each hand and one thrust through the belt of the user. The third Sai in the belt was a replacement for one either thrown or lost in combat. The prongs of the Sai were so designed to provide the skilled user with the capability of catching and locking the enemy’s weapon. Further, the skilled practitioner would generally utilize the weapons quick striking capabilities to attack an armed opponents hands, thus disabling and/or disarming him prior to moving in for the finishing techniques.

Tunfa:

Early Okinawans, at work gathering grain by the millstone, were nonetheless determined to continue their clandestine practice of the arts. The wooden handle normally wedged into a hole in the side of the millstone served their purpose well. This handle, known as the "tunfa or tonfa" was made of a tapered shaft of hardwood attached to a cylindrical grip projecting at a right angle from the shaft.

The handle could easily be dismantled from the millstone and brought into action. It was held by grasping the short grip loosely but firmly so that the weapon could not drop out of the users hand when manipulated. Most commonly, two tunfa were used, one in each hand. All use of the tunfa depends upon karate movements. The practitioner can punch or strike with great force, since the hardwood projection acts like an extension of the knuckles. By a quick flick of the wrist and arm, the user can reverse the Tunfa so that the longer end of the shaft will swing forward and strike the opponent with great force.

Good Tunfa techniques make judicious use of blocking and parrying actions. These actions and many of those involving the use of the Tunfa can be likened to those of the Sai. Today, Tunfa masters are rare in Okinawa, and there may be some chance of this art passing from the modern scene.

Kama:

The agricultural sickle has been used as long as man has grown rice. Seen in a number of different forms all over southeastern Asia, it has from earliest times served as an effective weapon in emergencies. On Okinawa, the sickle is called "kama", and was probably brought there during the numbered migrations from the Asian continent.

Kama tactics are primarily Okinawan, using the principles of Karate stancing and movement. some modifications had to be instituted in order that the user would not wound himself during manipulations of the weapon. The weapon has a hardwood handle and a blade that is crescent shaped and single-edged. This razor sharp blade can be pointed and hooked for hacking rather that for jabbing or skewering. The Kama is very effective in trained hands, but must be employed close into the opponent. Kama attacks incorporate chopping, hooking, hacking, striking, blocking, deflecting or covering actions against an enemy’s weapons or tactics. Kama are generally used in pairs, with a swinging pattern similar to propeller-like cover motions.

Kama techniques are difficult to master and for this reason it soon may become a dying art, remaining in the hands of senior students of a few highly experienced masters such as the late Seike Toma , Seikichi Odo and Shinpo Matayoshi.

Nunchaku:

The Nunchaku, a harmless-looking object appearing more like a toy than a weapon, is believed to have been first used as a horse bridle. The Nunchaku user can subdue an enemy by making use of ensnaring actions, crushing and holding techniques, poking or jabbing attacks, as well as defensive parrying, blocking and deflection actions.

The Nunchaku is a double-pieced hardwood weapon. The separate pieces of wood are connected by a cord or chain. Each piece is identical in shape being about one foot to fifteen inches in length and of square, hexagonal or octagonal cross section. The Nunchaku is used from Karate stances and attacks are delivered during close in fighting with the enemy. The Nunchaku is especially effective against weak points on the body. Painful ensnaring actions can be applied by catching the opponents fingers, hand or wrist in a "nutcracker grip" and closing the opened ends of the weapon with force. The most potent offensive technique are the powerful full range swings which can generate tremendous striking power at impact.

Eiku:

The Eiku or Eku Bo (oar) is a long shaft with a broad blade at one end used for rowing or steering a boat. The Okinawan Oar is made of wood. The Oar can be attached to oar hooks or oar locks,although it is more commonly held in the hands.

The Oar in the hands of a skilled practitioner becomes an excellent weapon employed somewhat like the Bo staff with the advantage of the broad flat end used for blocking, parrying, cutting and thrusting. Traditional Eiku bo katas employ repetitive "rowing movements" symbolic of their use in a fight while in a boat. Correct use of the Eiku bo is limited to only a handful of the older traditional masters in Okinawa. Old line masters such as the late Seikichi Odo noted that only one or two orthodox Eiku Bo forms exist, with most of the current katas being modern adaptations of the weapon to regular bo katas. In these modern versions much of the finesse moves with the weapon have been lost, with the emphasis placed on bo-like power strikes.

Nunte and Nunte Bo:

The Nunte is a weapon similar in size and design to the Sai, except that one of the prongs is reversed. The weapon is also sometimes called the Manji-sai. The Nunte can be utilized by a skilled operator in many of the same ways as the Sai, with the additional advantage of by-directional hooking capabilities, resulting from the reversed prong. The basic design for this weapon is similar to that of the Sai with the prongs off center, providing for one long and one short blade section.

The Nunte Bo is basically a regular bo with a Nunte tied to one end, serving as a fisherman’s gaff. It should be noted that the fighting techniques with the Nunte Bo differ significantly from those of the Bo alone. With the Nunte Bo, the skilled practitioner uses a lot more circular motion and rotation of the weapon in both attack and defensive techniques. The Nunte bo also adds the additional capability to deflect, parry, catch and lock the opponents weapon and to entwine the opponents clothing. The emphasis with the Nunte Bo techniques is with finesse rather than power.

Yari Bo:

The Yari Bo is a spear like weapon. It is used in many ways similar to the use of the bo. The additional advantage of this weapon it in its bladed or pointed end section which permits effective thrusting or slicing techniques. One significant difference between the regular Bo and the Yari Bo is in its length. Generally the Yari Bo length are longer, ranging from seven to ten feet in length.

Tekkos:

The Tekkos or Teko (claw) is a weapon originally devised by the Asian countries. The Tekkos are generally used in pairs. Tekkos can be made of wood or metal and may have small protruding points or blades. Use of the Tekkos employs slashing and clawing movements in addition to the normal punching techniques. the points/claws of the Tekkos would always be pointed toward the opponent. The Tekkos is primarily a close-in range weapon.

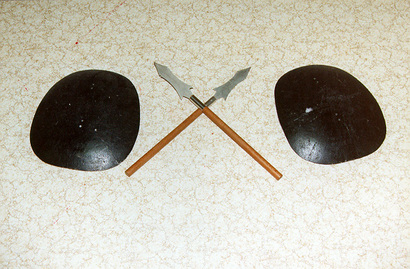

Tinbe and Rochin:

The Tinbe or Timbei is a shield and the Rochin is a short spear. The concept of the use of a shield and short or long spear is common to almost all fighting cultures around the world. The unique aspect associated with the Okinawan version is that the Tinbe (shield) made use of the shell of a turtle (large sea turtle) with a handle or straps fastened to the back to provide a hand grip on the shell. Other versions made use of a shield constructed of cane. Modern Tinbe are generally made of metal or fiberglass.

The Rochin was a short wooden shaft with a spear point or blade attached. Two renowned masters of the Tinbe and Rochin include the late Shinpo Matayoshi in Okinawa and Motokatsu Inoue in Japan. This art is not very widespread even in Okinawa today with its practice limited primarily to the major Kobudo organizations.

Kusarigama

The Kusarigama is basically an agricultural sickle, called Kama in Okinawa, with a cord attached to the end of the handle. There are a number of versions of the Kusarigama, with the biggest variation in the length of the handle and the size of the blade. Also in the larger versions, a weighted object is secured at the other end of the cord which permits the weighted end to be thrown at the opponent in an attempt to entangle him and then be able to move in for the finish. In Japan, the larger versions of the Kusarigama is the most popular, while in Okinawa the smaller versions are preferred. A noted practitioner of the "flying kama" techniques was the late Seike Toma in Okinawa.

Jo

The Jo or Hanbo (half-bo) were 4′ and 3′ variations of the Bo staff. They were often carried by the Okinawan royal court guards as it gave them an excellent weapon to use within cramped confines. A very practical weapon with a lot of modern day potential. Only a handful of kata exist which primarily come from the Taira or royal court guard traditions.

Tanbo

The Tanbo or Nitanbo were short wooden sticks most often used in pairs, measuring anywhere from 24" to almost 3 feet. The highly effective techniques, reminiscent of the Philippine arts, but simpler, see limited practice even in traditional Kobudo circles.

Kuwa

The Kuwa or wooden hoe is another minor weapon which is not often seen even in the most traditional of the kobudo schools. Probably the most noted practitioner of this weapon keeping the tradition alive was the late Shinpo Matayoshi of Okinawa.

LINEAGES OF OKINAWAN KOBUDO

As discussed earlier in this article, for most of the history of Okinawa Kobudo, its focus was to separate Kobudo Organizations apart from the Karate organizations. One of the first individuals to formally combine a traditional weapons lineage with a traditional karate style was the last Master Seikichi Odo. Master Odo taught the weapons program at Shigeru Nakamura’s dojo (his karate teachers school). Master Odo had received his kobudo training from some of the top current and past kobudo practitioners including: Kakazu, Matayoshi, Toma, Meazato, Kinjo, Kyan, Kuniyoshi and Sakiyama. Prior to the passing of Master Nakamura (the founder of the Okinawa Kenpo style) he asked Master Odo to continue to teach the kobudo program and to formally incorporate it into the karate program – thus the birth of Master Odo’s Okinawa Kenpo Karate Kobudo system in the early 1970’s. In recent years most of the major traditional karate systems now have also incorporated a program of formal weapons training.

Major lineages of traditional Okinawan Kobudo include the following:

TAIRA LINEAGE – This lineage traces its roots to Shinken Taira. Weapons taught include the bo, sai, manji sai, tunfa, kama, nunchacku, tekkos and tinbe. The majority of the Shorin-ryu, Isshi-ryu, Uechi-ryu and Japanese Kobudo trace their roots to this lineage.

MATAYOSHI LINEAGE – This lineage traces its roots to the teachings of Shinko Matayoshi. Weapons include a full range of the traditional Okinawan weapons with the addition of a number of Chinese basic weapons as well. A significant number of the Okinawan Kobudo practitioners trace all or part of their roots to this lineage.

UHUCHIKU LINEAGE – These teachings come from the famous Sai master Sanda Kanagusuku. This lineage teaches the sai, kai, tunfa, nunchaku, kama, tekkos and bo.

ODO LINEAGE – This is a more modern lineage coming from the teachings of Seikichi Odo and his Okinawa Kenop Karate Kobudo system. The weapons taught include the bo, sai, tunfa, nunchaku, kama, tekkos, eiku, nunte bo, yari bo, tinbe and rochin. This is also the lineage of the author of this article who was a senior student of the late Master Odo.

MOTOBU LINEAGE – These teachings come from the late Seikichi Uehara also was also noted for his teaching of the Okinawan Folk dances. The weapons taught include: katana, naginata, yari, tanto, bo, jo, tunfa, eiku and sai.

CHINEN LINEAGE – This lineage also referred to as “Yamani-ryu” traces their roots back to Sanda Chinen. The system was primarily a bo system, and the katas worked are worked by many of the Shorin-ryu and Goju-ryu practioners today.

KUNIYOSHI LINEAGE – This lineage also referred to as “Honshin-ryu” traces its roots back to Shinkichi Kuniyoshi, a famous weapons master. Weapons taught include the bo, sai, tunfa, and kama.

OVERVIEW OF TECHNICAL PRINCIPLES

One of the most important technical principles involved in the practice of Okinawan Kobudo is the "removal of target". By this we mean that the defender uses body positioning to cut an angle either defensively or offensively to the opponent, thus minimizing their vulnerability and maxamizing their offensive capability. In order to accomplish this, the defender must be able to adjust his stancing and movements to reflect and enhance the technical capabilities unique to each weapon.

A second important principle deals with the "control of centerline". Just as with the open hand arts, the individual who effectively controls the centerline has the greatest chance for success. Here again, stance adjustment is critical for the defender to maintain his/her control of the centerline – which lead one noted Kobudo Master (the late Seikichi Odo) to state that …"there are no stances in kobudo". Thus, while many martial artists commonly refer to Kobudo as …"being an extension of your Karate technique", it must be recognized that the "extension" is not one of basic Karate technique, but according to the author …"rather the enhancement of the underlying principles".

The difference in stancing between karate and kobudo is a very important distinction which is not readily recognized my most martial arts practitioners. One can not just take their standard karate (open hand) stances and techniques, add a weapon(s) and have “functioning kobudo”. Stancing is only a foundation for the weapons being used by the martial artist whether they are their open hands or their weapons. No one has ever won a fight solely based upon their stances, but many have lost a fight due to poor stancing resulting in lack of balance, power, etc. With the practice of Kobudo the stancing adjusts to the length of the weapon. With the long weapons such as the bo, nunte bo, yari, etc. the stancing is long and narrow permitting the end of the particular weapon to be able to control the centerline in a relaxed natural manner. With the intermediate range weapons such as the nunchaku, sai, tunfa and kama the stancing is still not as wide as ones normal karate stance (shoulder width). It is only with the short range weapons such as the tekkos, that the stancing approaches that used for ones open hand techniques.

The practice of traditional Okinawan Kobudo involves more than just performing a series of kata (forms). Like standard Karate practice, Kobudo practice also involves basic drills, bunkai (applications), disarms, throws, joint locking techniques and weapons sparring (fighting). In order to provide a level of safety for the practitioners, weapons fighting is performed with full body protective equipment in order to minimize the risk of injury. In addition, there are modifications made to the weapons to further promote safety such as taping over sharp weapons such as the blades of the kamas, or padding metal weapons such as the sai. The last and just as important part of Kobudo practice is learning how to defend against an opponent who has a weapon when you are unarmed. In order to use a weapons to its fullest as well as to be able to defend against a weapon, the student needs to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the weapon.

* * *

Hanshi Heilman, through his Heilman Karate Academy and International Karate Kobudo Federation (IKKF) is dedicated to the propagation of traditional Karate and Kobudo in order that the old ways will not be lost to the future generations of students. This article is just another step in the process of getting the history, techniques and principles of the "old ways" out to the serious martial arts public.

Thanks to Hanshi Heilman for participating in this exciting month of Admired Martial Artists. For more information on the schedule for the month, go here.

Where Do You Come From?

My grandmother is 90 years old and full of stories. I’ve heard them many times, but I’m always willing to listen one more time. There is great knowledge to be learned from the elders in our families, even if that means I sometimes need to listen respectfully to tirades about dogs who lick themselves too much. Yes, being opinionated (sometimes about very odd things) runs in the family.

Likewise, there is great knowledge to be learned from those who have gone before us in our karate families. There are certain martial artists that you meet that have a special something about them. You feel that just by being around them, you’re gaining knowledge. They seem to have a calming effect on those around them. It is obvious that they possess great knowledge.

This weekend, I was able to sit down with the 9th degree black belt who runs our karate school (He also heads up the entire style of Okinawan Kenpo and Kobudo in the US). He’s an excellent teacher, good with children and adults alike. He’s patient, knowledgeable and possesses that certain something that you can’t quite put your finger on, but you just know is something important. In his book "My Journey with the Grandmaster" Kyoshi Hayes calls this quality "hinkaku" which means "the dignity of a senior."

I can’t tell you how happy I am that I asked him how he got his start in the martial arts. What followed that question was quite a story. It’s his story to tell, so I won’t go into details, but finding out details about my instructor and his instructors, what it was like in Okinawa, and how the martial arts traveled to the states was fascinating.

I know many people who take karate classes in all kinds of different styles. What I find most interesting is that if you ask people what style they study, and where it came from, most people have very little information. Maybe some feel that history lessons aren’t necessarily important to their study of the martial arts. Maybe some just never thought to ask. Personally, I see this knowledge as a piece of the puzzle. Without it, your training just isn’t quite complete.

Patience

Filed under: ACL Hell, Mental Strain for Mama, Tales from the dojo

Last week, I watched Big I’s karate classes from the sidelines. The desire to get back out on the floor again is so strong that I began daydreaming about whether or not I’d be able to balance by putting most of my weight on one foot in order to do drills where you don’t have to move your legs much. I thought about putting a chair out on the floor so that I could sit there and do the arm movements. I thought about what good exercise it would be to just balance on my right leg during class for all the drills. I could do cat stance, I reasoned with myself.

My daydreams were then interrupted by Big I’s one instructor. He asked me if I could work with one of the little girls on her punch from the sidelines. Her punches were not going to the solar plexus. Instead they were being thrust out there at about shoulder height in a very haphazard fashion. While the instructor continued with the other kids, this little girl sat beside me and we worked on punches.

I told her to watch herself in the mirror and aim for her belly. The punches were still going up to her shoulders and beyond. So, I showed her how her gi comes to an "x" almost right at the perfect punch spot. I told her that was her target, and to look at herself in the mirror and punch that "x" every time. It seemed to click; and I sent her back out on the floor to practice the next skill.

It was a nice little distraction from my daydreams, and it felt good to help someone else instead of having everybody help me all the time. I’m not playing the role of the injured girl very well. I’ve been trying to walk around without my crutches entirely too much, because it’s so frustrating to not be able to do things for myself. It’s impossible to carry a drink up to the living room when both hands are holding onto the crutches. Although being waited on was initially nice, it’s now very annoying to have to rely on other people all the time. For my independent thinking in the form of walking without crutches around the house sometimes, I paid for it yesterday.

My knee hurt terribly. At the end of the day, I sprawled out on the floor on my stomach to have Mr. BBM inspect the back of my knee. The back of my knee is SO sore. It’s sore to the touch and some of the exercises were really hurting it too. Mr. BBM said I was a little swollen. I asked him to get me some ice and attempted to get off the floor without asking for help. My knee shifted and that horrible pain shot through my knee. It hurt so bad that my eyes teared up. It’s moments like this that I’m very skeptical about being about to rehabilitate my knee without surgery. It just feels so wrong in there.

I have three more weeks of physical therapy, and then I see the surgeon again. He said that if we decide to do surgery he will get me in within a week or two. Let’s do the math: appointment on the 7th, surgery by the 14th or 21st. Christmas is the 25th. If that’s the case, I am going to have one incredibly miserable Christmas. Not knowing what’s going to happen is also driving me insane.

I told Mr. BBM that I feel like my life is on hold. My plans to test for Shodan, that had been so meticulously mapped out in my head, are now completely up in the air. With the way I’m feeling now, I can’t even imagine going up for testing in February; and if I do have surgery, summer is probably out of the question too.

Lil C is two years old and when Big I was this age, I used to wear holes in the knees of my jeans all the time. I spent so much time crawling around with her and playing with her; and I absolutely hate that even sitting on the floor to play with her is uncomfortable right now. I hate it even worse that carrying her around isn’t an option. She’s only little for so long; these years fly, and I don’t want her early memories to be of her Mommy on crutches.

I was feeling all sorry for myself last night after I twisted my knee, and I asked Mr. BBM why he thought this was happening. Is there a reason for this? If everything has a purpose, then what is the purpose of this? Mr. BBM said, when I first did this to my knee, that this is the perfect piece of "drama" for my eventual book. You know, the part in the book where people’s jaws drop and everyone wonders, "Will BBM get her shodan? Will she be able to do the martial arts again?" and so they keep turning the pages faster and faster to find out. I wish that I could skip to the end chapter and know how it’s all going to work out. For now, it’s just a work in progress and the ending is very uncertain.

As I was getting ready to leave the dojo the other night, one of my instructors said to me, "Injuries teach us patience." I’ve always believed that there is more to the martial arts than just the physical aspects. If the martial arts isn’t just about kicking, punching and technique, then maybe that is why this is happening. Apparently, I’m getting a very well-rounded martial arts education. Lesson #58: Patience.

***The latest review is up at The BBM Review. In the weeks to come, look for more book reviews, toy reviews, website and learning software reviews, and hopefully some cool new video game reviews as well. If you like the reviews, please consider adding us to your blogroll, and bloglines subscriptions. We appreciate your support as we continue to receive growing interest from many companies.

***In case you’re looking for the comments, I closed them on this entry. Just because I’m feeling sorry for myself doesn’t mean I expect you to.

BBM brings you “Pimp My Crutches”

So I can’t walk. That doesn’t mean I can’t go to observe a Black Belt Workout, and that’s just what I did (Thanks to Mr. BBM who pretty much kicked me out of bed and the house today to make me go, and Hanshi who invited me to come and watch). Unlike when I’m gi’ed up, I arrived a little late. The workout was already in full swing.

I crutched it up the stairs and when one of the Kyoshi’s at our school saw me, she started clapping. She followed that with a shout of "Now THAT’s SPIRIT!" and the entire dojo started clapping and cheering. I wasn’t expecting a standing ovation (o.k. not really a standing ovation since they were already on their feet anyway, but an ovation none-the-less), but that’s just what I got.

I smiled and thanked them and then spent a good part of the workout talking to Kyoshi about good martial arts books, and our soon-to-begin book discussion group. Our first two books which are going to be discussed simultaneously are "Living the Martial Way" by Forrest Morgan (which I’ve already read but will gladly dig into again) and "On Killing" by Dan Grossman. Although I’m sure the idea of a dojo book discussion group has probably been in the works for quite some time, I like to think that it’s Kyoshi’s way of keeping me involved and included even when I’m sidelined, and that makes me feel incredibly good.

Despite only being at my new dojo for a couple months, I can honestly say that I feel a part of the family; and I am honored to be included in such a stellar group of people. But enough about that before I get all teary and sentimental. . .

After the workout, I met Mr. BBM at the local fabric store. I started with ordinary wooden crutches, with uncomfortable rubber grips and armpit rests. After a day, Mr. BBM strapped some Warrior shin guards on the top and that was o.k. My Mom took it a step further by replacing the shin guards with egg crate foam secured with duct tape. But egg crate and duct tape do not a pretty crutch make.

I’m sure most of you have heard of MTV’s "Pimp My Ride" which is a makeover show where professionals take beat up cars and turn them into extraordinary vehicles. Today was my very own version of that show except my "ride" these days are my crutches. Keep in mind that I’ve called in a favor to a friend who owns a Japanese painting kit, who also knows how to write "Nintai" in Japanese. That will be forthcoming to my already pretty awesome crutches.

I give you the before picture. . .

And the after Asian-inspired crutches. . .

Since a girl needs more than one look. . .

In case you’re wondering, Mr. BBM and I made these without the use of a single piece of thread or a needle. The pretty floral covers go over top of the asian fleece covers and it all fits over top of the foam and duct tape concoction. There are also matching hand-grips in case you were too wowed by the top to notice the bottom. Just in case you can’t tell from the photos. . . my new and improved crutches are FAB-U-BBM-LOUS.

If I’m going to have to use them for a while, they might as well be pretty and cool, right?

Calm

Mr. BBM practically kicked me out of the house today. He knew I needed to get out. Today, Lil C used me as a human tissue on there separate occasions. She also took her own diaper off, sat on her little potty for a minute, and then forgot why she was sitting there, got up and peed on the floor. Later, she pooped, and before I could hobble around to get the stuff and change her, she shoved her hand down her diaper. I’ll leave it at that. It was a rough day.

So I took Big I to the dojo by myself. I crutched it up the stairs and began talking to the Kyoshi matriarch of the entire organization. She is the second highest ranking black belt in our organization with an 8th dan. We began talking about my knee, the options and all the women who are experiencing acl injuries in the martial arts (I’m the second one in the past few months in our organization).

For the first time since this happened, I felt a sense of calm. Talking to Kyoshi has that effect on you, and it certainly did for me. As class got underway, I chatted quietly with some of the parents. One of the women blew her acl out while playing softball and had surgery for it many years ago. She was sharing her experience with me. Another woman there has worked at the hospital with the Orthopedic doctors and she confirmed that I had made a good choice with the group I chose. It was like everyone there addressed and erased a little piece of worry that I had and helped it just melt away.

While sitting on the sidelines, I took the opportunity to really watch the way my instructor moves. I was able to watch Big I too. I joked with some of the other parents that we need to call in the guys from The Unit to rig us up with little ear pieces we can stick behind our kids ears so that we can communicate with them from the sidelines. "Bend your knees. Get into Seisan!" etc. etc.

At one point during class, my instructor talked about a friend of hers who had been in a terrible car accident. In bed with her injuries, she concentrated on doing the breathing from Sanchin, and it helped her recover faster. She talked about how her friend would practice the arm movements for kata and waza while in bed to pass the time and keep her techniques in her head, also to keep her sanity. She nodded in my direction.

I am so glad that I went to the dojo tonight. I felt peaceful and relaxed for the first time since I got this nasty injury. It was a nice change of pace. We’ll have to see how long I can keep the calm up.