Why Your Child is Not a Black Belt

Filed under: Admired Martial Artists Month, Guest Post, Tales from the dojo

By: Ann-Marie K. Heilman, Kyoshi

Okinawa Kenpo Karate Kobudo

Heilman Karate Academy, Inc.

To the uninformed person on the street or perhaps the new student in the dojo, all black belts may seem alike. The parent of a child whose classmate at school is an 8-year-old third degree black belt may have the feeling, “What is holding up my child’s progress?” Are all schools alike? Is there one course of study that, when followed will end with the coveted “black belt?” Or is one school easier than another? Is one school really that different from another? The answer to a traditionalist is a resounding YES! We need to do some fact finding.

In the Okinawan/Japanese systems, wearing a black belt is a sign of maturity; in other words, the student has demonstrated mature physical growth, knowledge of the physical basics of their system, has demonstrated over time an ability to make sound judgments thus revealing mental maturity. None of this is accomplished very quickly even if the student is an adult.

When we discuss techniques in class we judge a student’s ability and knowledge and expertise of technique compared to an attacker. In adults, body size usually does not change drastically. With children’s growing bodies techniques must change as their bodies change; their arm and leg length for example, as well as their height, will render some techniques useless or perhaps better depending upon their current physical size. This generally is not true for adults who reach their maximum growth by the late teens and will stay there for years.

When we consider adult versus child judgment or mental maturity we find a difference. Why consider sound judgment as a marker of black belt eligibility? Think about self-control or quick judgment in a street situation. There are adults who should not study martial arts. They haven’t learned self-control. They lose their temper, use martial arts as a "power game" over others or do not use good judgment in everyday matters. Certainly martial arts can provide them with an opportunity to learn these virtues but that depends on the quality of instruction, which is factor of the school they attend. And all schools are not alike.

In terms of the definition of a "black belt" there are many different ideas. Some systems promote individuals who are good athletes and can kick high, punch hard, and/or win trophies. There is nothing wrong with this idea, but a traditional view of the rank implies mental maturity. This does not come early in a person’s life but develops slowly over time.

We know of many kids who are excellent in the physical aspects of their art and we might call them "junior black belts” to recognize their proficiency, but they are still children. Can they teach? Sometimes. I have known a few children who can convey information better than some adults. Can they make sound judgments about people? Sometimes. But not always. That takes experience and maturity. Should we "hold them back" until they are 16? Usually, but not always. At many traditional dojos those individuals who demonstrate ability can be recognized by awarding them a junior black belt. However, full ranking is generally held off until maturity has been demonstrated and that does not come easily or quickly.

Curriculum is another matter. As a traditional dojo, the HKA offers a full program of okinawan karate and Kobudo (weapons). From basics (stances, kicks, blocks, strikes), through self-defense, sparring, to participating in demonstrations, tournaments, and dojo events – we cover a lot of material.

Sport karate is a new development that came into existence in America in the "60’s. It has blossomed and grown into a billion dollar business. It is a lot of fun and those who have accumulated a number of trophies will tell you the great feeling of accomplishment they have when they win. But sport karate is different from traditional karate where "points" don’t matter; your performance and development as a person in mind, body, and spirit does. There is much more to say on this matter and we will continue the discussion in future blogs.

Where Will We Take the Martial Arts?

An Exploration Into the Classical Ways of Training

BY: MATTHEW APSOKARDU

The world is arriving at a critical point in martial arts transmission. Fewer and fewer original masters remain from direct Asian lineages of the various fighting arts. Leading the way now is the first generation of global students. These soldiers and students from the U.S., along with areas like Europe and Australia, are becoming the key to proper transmission of classical martial arts.

While these few men and women struggle to transmit their knowledge fully, they must battle against the behemoth that is modernization and capitalism. Karate and tae kwon do schools pop up in every strip mall, offering quick belts and flashy techniques with no obligation required except monetary compensation.

Nor can we underestimate the impact of Mixed Martial Arts. MMA offers an eclectic amalgam of techniques while forgoing activities like kata. MMA has produced many great fighters and is a legitimate form of combat exercise – but also steers many potential students away from traditional training.

Truly, it is up to the next generation, the kyu ranks and lower dan ranks of every style, to learn how to learn the old way; to refuse the easy gratification of trophies, money, and false notoriety and pursue the intangible goals of the past.

The big question is – how do we go about training classically?

The following are a few quick tips with that goal in mind. This is a very sparse list; simply some key points that I believe are important and that I continue to work on personally. This is not an analysis of techniques, nor is it a guide to sparring. But for those seeking something of the old budo heart, it may be helpful.

In trying to keep things "old style", I would like to break down my suggestions in traditional karatedo fashion – Body, Mind, and Spirit.

TO TRAIN YOUR BODY:

Stick Around

If you want to get anything out of a classical style, you have to stick around. Six months won’t cut it. Six years won’t cut it. The way old-style teaching operates is through repetition and muscle memory. After developing a rock solid foundation, instructors will then teach you how to work outside of kata and routine drills. But if you ditch once you get a first degree black belt, all you’ve got is a couple of prearranged exercises. Not very useful against a live opponent.

Many of the most advanced techniques found in old arts are just extraordinarily refined basics. Strikes made with perfect timing at precision targets, delivered in a strategic order, result in some stunning effects (if you’ll excuse the pun). It takes a while to learn these targets, and even longer to utilize them correctly against free-willed opponents who don’t feel much like getting hit.

The best way to ensure ‘sticking around’ is to first realize what you want in a core style. Look into different styles and realize which fits your lifestyle and body type. Once you’ve established that, keep it your core style and develop around it (to learn more about this training theory, consult Forrest Morgan’s "Living the Martial Way.") Remember, sports are sports. Some schools simply don’t teach classical theories, so if you want them, keep looking.

Investigate

Do your homework! Don’t cringe, just do it. Actually…cringe. The martial art universe is epically large and hard to put together. When you first begin studying, it will seem all but impossible to put your own style’s history together, let alone how it interacts with all the other styles, and how those styles interact with other countries, and so on and so forth. Even now when I think about the vast martial scape it makes my head spin. But the old masters made it their business to know such things, and so must we. Not to mention, by reading from credible sources and watching videos of legitimate masters, any martial artist’s eyes can be opened to an array of concepts and ideas they never considered before; and the best part is, it doesn’t matter what rank you are. There WILL be something to learn.

Remember, the old Okinawan sensei intermingled their ideas and techniques. They bounced concepts off of each other in the hopes of refining their systems. They learned from multiple instructors and utilized those techniques that worked best (yes, it’s true. You eclectic folk can remind your hard-lining friends).

TO TRAIN YOUR MIND:

Don’t Obsess Over Rank

Ranking in martial arts started off innocently enough – Jigoro Kano wanted to gauge the progress of his students. Unfortunately, rank has become a bit of a monster and brings out negative qualities in a lot of people. Many lust after rank. Many abuse it once it’s attained. Others will cheat and barter just to get it. This is not at all what was originally intended.

The old budo styles were used to prepare samurai, and to a lesser extent soldiers, for battle. Sword cuts, empty hand techniques, spear thrusts…as much as they could pack into the minds of the combatants before war began. There was no time and no need for rank because one simple factor evaluated your skill level – whether or not you lived.

It’s ok to feel grateful and honored as rank comes to you, but putting more stock in it than that can lead to some of the troubling situations we see abundant today.

Optimize your mental acuity

Mental prowess is very valuable. Being able to effectively process that which you see and how you react is one of the benefits of martial art training. But there is a lot more to it. Mushin is a term that roughly translates to "no mind" and refers to a complete readiness and quieting of the mind. When a karateka effectively utilizes mushin, processing what you see and reacting is no longer necessary - there is simply reaction. Beyond mushin is zanshin, roughly translated as "remaining mind." Zanshin helps keep a martial artist aware of his surroundings at all times and alert for that which may come. One who utilizes zanshin is aware of the position of the sun, the condition of terrain, and every movement of his opponent. Forrest Morgan equates it to a wolf that hovers over his opponent, teeth bared and ready to break his opponent’s neck at the first sign of movement.

One who trains in mushin and zanshin may begin to develop the Budo ideal of Shugyo No Mokuteki. Or as Miyomoto Musashi explained it, "a mind as high as Mt. Fuji…you can see all things clearly. And you can see all the forces which shape events; not just the things happening near you." By developing your mind in this manner, conflict can be resolved or avoided before it begins.

In order to reach mushin a heavy emphasis on kata should be maintained. Kata can be a mobile form of meditation and teaches the body, through extensive repetition, to move without conscious thought.

To reach zanshin, a martial artist must carry their art with them at all times. They must constantly analyze scenarios, environments, body language, and ‘gut feelings’ experienced in the hara (lower abdomen region). This, combined with dojo training and kumite, is critical.

Explore without Deviation

One of the biggest complaints about older arts is their seemingly stodgy nature. Moves in kata seem quaint and unrealistic. They appear completely unresponsiveness to the ever-changing nature of attackers.

That’s true…if you never explore. Kata, or prearranged attack-defense sequences, are useful as learning devices. The concepts in each kata are carefully devised, multipurpose actions that, once ingrained in the mind, can become infinitely useful. Once technique and good habits are reflexive instead of thought-induced, the practitioner can more fully explore the art (and thus scenario, intent, opponent, and other variables are opened up for consideration).

Unfortunately, problems arise with hardcore explorers. Sometimes, they fall in love with their own interpretation and decide to change kata and material entirely. These people believe they are changing things for the better. For that specific person, maybe it is better. But kata and traditional arts are designed to train everyone, and can flex for specific needs, but must be flexed back to their original form if they are to be sustained for future students.

Think of kata as a book. You first read the words in the book, but then your imagination takes hold and creates a whole world around those words. You wouldn’t go changing the words to better fit your imagination would you? No, because then the next reader won’t be able to explore the original masterpiece.

TO TRAIN YOUR SPIRIT:

Realize the Purpose

Karate and other traditional arts are not simply about fighting. They are about Life Protection (if I may borrow a term from a writer later in this month – Kyoshi Bill Hayes). The classical martial artist protects those around him/her and even protects the lives of wayward attackers by withholding technique as much as possible; but if the situation demands it, responds with devastating consequences. Furthermore, practitioners of do arts (karatedo, judo, taekwondo, kyudo, kendo, iaido, hapkido, aikido, etc.) concern themselves with following "the way."

On the surface, "the way" of any martial art is simply the unique approach that art takes toward combat. "The way" of aikido involves melding with an opponent’s energy and using their own force against them. "The way" of tae kwon do is the utilization of both hand and foot techniques, but with a strong emphasis on kicking. These stylistic differences are notable, but not really the reason the old masters placed do on the end of their arts. Instead, they intended "the way" to be a path in which students could build their character and reach self actualization.

To better understand such character building, here are just a few precepts written by Funakoshi Gichin, founder of Shotokan Karate and considered the father of Japanese karate:

– Karate-Do strives internally to train the mind to develop a clear conscience, enabling one to face the world honestly, while externally developing strength to the point where one may overcome even ferocious wild animals. Mind and technique become one in true karate.

– Just as it is the clear mirror that reflects without distortion, or the quiet valley that echoes a sound, so must one who would study Karate-Do purge himself of selfish and evil thoughts, for only with a clear mind and conscience can he understand that which he receives.

– He who would study Karate-Do must always strive to be inwardly humble and outwardly gentle. However, once he has decided to stand up for the cause of justice, then he must have the courage expressed in the saying, "Even if it must be ten million foes, I go!" Thus, he is like the green bamboo stalk: hollow (kara) inside, straight, and with knots, that is, unselfish, gentle, and moderate.

– To win one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the highest skill. To subdue the enemy with out fighting is the highest skill.

– When you look at life think in terms of karate. But remember that karate is not only karate — it is life.

In order to better understand Funakoshi Sensei, we must scrutinize all of our actions, even when no one is looking. We have to let the perfection we strive for in technique infect the way we think, so that flaws in character are slowly chipped away through the power of will. Anything less falls short of our founder’s ideals. Furthermore, we need to remind ourselves that martial arts are a lifelong endeavor, and no matter what, there is always a way to improve.

In our modern time, transmission of these classical ideals can be very difficult. Parents bring children to various dojo in order to learn self-defense, not to be preached at. Furthermore, they are concerned that Asian philosophies that resemble Shinto and Buddhism will interfere with their chosen faith. Generally, the concept of ‘respect’ is well received; but once ‘honor’, ‘humility’, ‘veracity’, etc. make an appearance, the acceptance isn’t as ready. It’s a very tricky mire to navigate, and that is why every student must take it upon themselves to study and investigate such concepts on their own. If they’re lucky, they will meet an instructor who is willing to help them along the way.

Consider Body/Mind/Spirit

Separately, each is useful; but it’s the harmonic coordination of the three that makes a classical martial artist. If one branch exists without the other, the journey is incomplete. Only by training in all three can we achieve that indescribable characteristic so noticeable in the old masters – Heijo Shin: A peaceful mind.

In Conclusion – "Part the Clouds, See the Way"

This may all sound like a bit much. No lie, it’s a handful. But the senior teachers out there right now went through the same ordeals, and even more. It’s up to us, the lower ranks, to receive as much of their knowledge as we can and to avoid slipping off the right path. I don’t write this as one who has accomplished everything, but as one who struggles alongside you. Hopefully, together, we can all keep the true nature of the martial arts alive!

MA

An Overview of Okinawan Kobudo

Filed under: Admired Martial Artists Month, Guest Post, Tales from the dojo

BY: C. BRUCE HEILMAN

Today most people involved in the martial arts and even many of the general public have become aware of some of the martial arts weapons. Probably, the most widely known of the Okinawan weapons is the Nunchaku, which received its notoriety in numerous martial arts movies during the 1970’s and 80’s. Others may to a lesser extent be aware of the Bo, Tunfa and Sai. However, there exist a number of other significant weapons to traditional Okinawan Kobudo that the knowledge of which is limited to the most serious Karate/Kobudo practitioners.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT

The study of ancient martial arts weapons, and their related techniques, has over the centuries resulted in the development of a variety of schools and systems. These systems can be divided into two basic groups purely for combative purposes: 1) Bugei – martial arts, and 2) Budo – martial arts. The Budo form was developed from the Bugei and Jitsu forms. The Okinawans call these forms "KOBUDO", or ancient weapons arts.

Around 400 years ago, Japan began to assert control over the Island of Okinawa. One of the edicts forced the Okinawan people to turn over their weapons to the Japanese. The move was made by Imperial Japanese leaders with almost no realistic political foresight and very little insight or perception into the Okinawan way of thinking. The ruling classes assumed that to gain political and financial control over this tenacious island race, all that was necessary was to disarm the people. The edict specifically ordered that "all weapons" be turned over to the authorities. Little did the authorities realize that the Okinawan people were such a nationalistic race and so strongly devoted to freedom that they would go to any lengths to deceive and/or hide the weapons they needed to fight their oppressors. Thus, weapons were called "farm implements", but underground the fighting population was training in the use and proficiency of these tools. Soon the weapons masters became a most feared force in the battle for political freedom, feared by the Japanese and idolized by the Okinawan people whose protectorate they were.

Today, much of the Island of Okinawa has undergone its own industrial revolution, and most of these crude farm implements have been replaced by mechanical and power tools. Yet, the history of these weapons is still part of the rich traditional background of Okinawan Martial Arts, and as important physical aspect of the arts.

Kobudo practitioners today, as did their ancient predecessors, perfect weapons techniques by training with kata specifically designed to teach and perfect directional movements, transitional movements, body alignment, balance, grace and coordination between body and weapon.

The practice of Okinawan Kobudo, although not formally part of Karate, is almost inseparable from an historical viewpoint. Okinawan Karate practitioners are generally involved to some extent in the practice of Kobudo. While most are at least proficient with a few weapons, few if any can use a wide range of weapons with a high level of proficiency.

The major difference between Karate and Kobudo practice has been that historically, Kobudo practice has not been as systematized as with Karate. Kobudo practice has tended to be focused upon separate "Kobudo Associations". The very existence of these Kobudo associations has however, over time started a trend towards systematization of the Kobudo training, techniques and katas. Examples of such Kobudo Associations include: Shinpo Matayoshi’s Zen Okinawa Kobudo Renmei ; the late Eicho Akamine’s Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinko Kai ; Seikichi Uehara’s Motobu-ryu Kobujitsu Kyokai ; and Motokatsu Inque’s Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinko Kai.

Also, the within the last twenty years we have seen the emergence of combined Karate-Kobudo organizations which have furthered the trend toward systematization of the Kobudo training. One of the earliest was Seikichi Odo’s Okinawa Kenpo Karate-Kobudo Renmei. Other such combined organizations include: Kenko Nakaima’s Ryuei-ryu Karatedo Kobudo Hozon Kai ; Seitoku Higa’s Zen Okinawa Karate Kobudo Rengo Kai ; Choboku Takamine’s Kokusai Karate Kobudo Tenmei ; Ryusho Sakagami’s Itosu Kai, Nihon Karatedo Kanto – Hanbuncho of Hozon Shinko Kai ; Tsueneyosho Ogura’s International Karate and Kobudo Propagation ; and Masafumi Suzuki’s All Japan Budo Federation.

WEAPONS OF OKINAWAN KOBUDO

The major traditional weapons of Okinawan Kobudo include the following:

- Bo

- Sai

- Tunfa

- Kusarigama

- Kama

- Nunchaku

- Eiku

- Jo

- Nunte Sai

- Nunte Bo

- Yari Bo

- Tanbo

- Tekkos

- Tinbe

- Rochin

- Kuwa

A brief introduction to each of these weapons of Okinawan Kobudo is presented in the following discussion.

Bo:

The Bo is one of the most popular weapons of Okinawan Kobudo. In the hands of Masters such as Seikichi Uehara, Shinpo Matayoshi and Seikichi Odo, it was almost an unbeatable weapon due to its reach and striking power. Formally called the "Rokushakubo", where "roko" means six, "shaku" is a unit of measurement of about a foot in length, and "bo" means staff.

As an art form, Kobudo is closely tied to Karate, adopting from the Chinese the basic principles but developing its own Okinawan characteristics. The first of these is the matter of the design of the weapon. The Okinawan Bo is tapered at both ends to provide a more centralized focus for striking the opponent’s body.

The use of the Bo relies heavily upon a good knowledge of karate basics. The Bo operates best from outside the opponent’s weapons swing zone, and it gives its user a strong advantage over an opponent’s shorter weapon. When used at a close range, within the opponents swing zone, the Bo provides a variety of blocking and parrying techniques, but loses some of its distance advantage.

Bo training requires the student to make a lengthy study of the fundamental grips, stances, movements and techniques of striking, blocking, poking, thrusting and disarming. It must be noted that to effectively be able to utilize the Bo to its maximum, the student must be able to use the full range of the weapon.

Sai:

The Sai is a uniquely designed short metal weapon with a long history. Found in India, China, Indo-China, Malaya and Indonesia, its presence in Okinawa probably derives from migration from one or more of these sources. Prototype designs may be seen in the Trident-shaped weapons of ancient times. The ancient Indonesian civilizations on Sumatra and Java, which had contact with Okinawa used the weapons in their fighting arts.

The Sai is primarily a defensive weapon and is effective against an enemy armed with blade, staff or stick. The length of the Sai varies with the most popular lengths between 15-20 inches. It was generally made from iron or steel and weighed between one to three pounds. The Sai is generally used as a truncheon, although its earlier forms derived from a bladed weapon. The Sai may be used to deflect, block, or parry a cutting or thrusting attack of a bladed or staff weapon.

The Sai were usually carried, one in each hand and one thrust through the belt of the user. The third Sai in the belt was a replacement for one either thrown or lost in combat. The prongs of the Sai were so designed to provide the skilled user with the capability of catching and locking the enemy’s weapon. Further, the skilled practitioner would generally utilize the weapons quick striking capabilities to attack an armed opponents hands, thus disabling and/or disarming him prior to moving in for the finishing techniques.

Tunfa:

Early Okinawans, at work gathering grain by the millstone, were nonetheless determined to continue their clandestine practice of the arts. The wooden handle normally wedged into a hole in the side of the millstone served their purpose well. This handle, known as the "tunfa or tonfa" was made of a tapered shaft of hardwood attached to a cylindrical grip projecting at a right angle from the shaft.

The handle could easily be dismantled from the millstone and brought into action. It was held by grasping the short grip loosely but firmly so that the weapon could not drop out of the users hand when manipulated. Most commonly, two tunfa were used, one in each hand. All use of the tunfa depends upon karate movements. The practitioner can punch or strike with great force, since the hardwood projection acts like an extension of the knuckles. By a quick flick of the wrist and arm, the user can reverse the Tunfa so that the longer end of the shaft will swing forward and strike the opponent with great force.

Good Tunfa techniques make judicious use of blocking and parrying actions. These actions and many of those involving the use of the Tunfa can be likened to those of the Sai. Today, Tunfa masters are rare in Okinawa, and there may be some chance of this art passing from the modern scene.

Kama:

The agricultural sickle has been used as long as man has grown rice. Seen in a number of different forms all over southeastern Asia, it has from earliest times served as an effective weapon in emergencies. On Okinawa, the sickle is called "kama", and was probably brought there during the numbered migrations from the Asian continent.

Kama tactics are primarily Okinawan, using the principles of Karate stancing and movement. some modifications had to be instituted in order that the user would not wound himself during manipulations of the weapon. The weapon has a hardwood handle and a blade that is crescent shaped and single-edged. This razor sharp blade can be pointed and hooked for hacking rather that for jabbing or skewering. The Kama is very effective in trained hands, but must be employed close into the opponent. Kama attacks incorporate chopping, hooking, hacking, striking, blocking, deflecting or covering actions against an enemy’s weapons or tactics. Kama are generally used in pairs, with a swinging pattern similar to propeller-like cover motions.

Kama techniques are difficult to master and for this reason it soon may become a dying art, remaining in the hands of senior students of a few highly experienced masters such as the late Seike Toma , Seikichi Odo and Shinpo Matayoshi.

Nunchaku:

The Nunchaku, a harmless-looking object appearing more like a toy than a weapon, is believed to have been first used as a horse bridle. The Nunchaku user can subdue an enemy by making use of ensnaring actions, crushing and holding techniques, poking or jabbing attacks, as well as defensive parrying, blocking and deflection actions.

The Nunchaku is a double-pieced hardwood weapon. The separate pieces of wood are connected by a cord or chain. Each piece is identical in shape being about one foot to fifteen inches in length and of square, hexagonal or octagonal cross section. The Nunchaku is used from Karate stances and attacks are delivered during close in fighting with the enemy. The Nunchaku is especially effective against weak points on the body. Painful ensnaring actions can be applied by catching the opponents fingers, hand or wrist in a "nutcracker grip" and closing the opened ends of the weapon with force. The most potent offensive technique are the powerful full range swings which can generate tremendous striking power at impact.

Eiku:

The Eiku or Eku Bo (oar) is a long shaft with a broad blade at one end used for rowing or steering a boat. The Okinawan Oar is made of wood. The Oar can be attached to oar hooks or oar locks,although it is more commonly held in the hands.

The Oar in the hands of a skilled practitioner becomes an excellent weapon employed somewhat like the Bo staff with the advantage of the broad flat end used for blocking, parrying, cutting and thrusting. Traditional Eiku bo katas employ repetitive "rowing movements" symbolic of their use in a fight while in a boat. Correct use of the Eiku bo is limited to only a handful of the older traditional masters in Okinawa. Old line masters such as the late Seikichi Odo noted that only one or two orthodox Eiku Bo forms exist, with most of the current katas being modern adaptations of the weapon to regular bo katas. In these modern versions much of the finesse moves with the weapon have been lost, with the emphasis placed on bo-like power strikes.

Nunte and Nunte Bo:

The Nunte is a weapon similar in size and design to the Sai, except that one of the prongs is reversed. The weapon is also sometimes called the Manji-sai. The Nunte can be utilized by a skilled operator in many of the same ways as the Sai, with the additional advantage of by-directional hooking capabilities, resulting from the reversed prong. The basic design for this weapon is similar to that of the Sai with the prongs off center, providing for one long and one short blade section.

The Nunte Bo is basically a regular bo with a Nunte tied to one end, serving as a fisherman’s gaff. It should be noted that the fighting techniques with the Nunte Bo differ significantly from those of the Bo alone. With the Nunte Bo, the skilled practitioner uses a lot more circular motion and rotation of the weapon in both attack and defensive techniques. The Nunte bo also adds the additional capability to deflect, parry, catch and lock the opponents weapon and to entwine the opponents clothing. The emphasis with the Nunte Bo techniques is with finesse rather than power.

Yari Bo:

The Yari Bo is a spear like weapon. It is used in many ways similar to the use of the bo. The additional advantage of this weapon it in its bladed or pointed end section which permits effective thrusting or slicing techniques. One significant difference between the regular Bo and the Yari Bo is in its length. Generally the Yari Bo length are longer, ranging from seven to ten feet in length.

Tekkos:

The Tekkos or Teko (claw) is a weapon originally devised by the Asian countries. The Tekkos are generally used in pairs. Tekkos can be made of wood or metal and may have small protruding points or blades. Use of the Tekkos employs slashing and clawing movements in addition to the normal punching techniques. the points/claws of the Tekkos would always be pointed toward the opponent. The Tekkos is primarily a close-in range weapon.

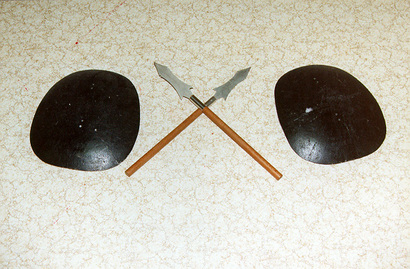

Tinbe and Rochin:

The Tinbe or Timbei is a shield and the Rochin is a short spear. The concept of the use of a shield and short or long spear is common to almost all fighting cultures around the world. The unique aspect associated with the Okinawan version is that the Tinbe (shield) made use of the shell of a turtle (large sea turtle) with a handle or straps fastened to the back to provide a hand grip on the shell. Other versions made use of a shield constructed of cane. Modern Tinbe are generally made of metal or fiberglass.

The Rochin was a short wooden shaft with a spear point or blade attached. Two renowned masters of the Tinbe and Rochin include the late Shinpo Matayoshi in Okinawa and Motokatsu Inoue in Japan. This art is not very widespread even in Okinawa today with its practice limited primarily to the major Kobudo organizations.

Kusarigama

The Kusarigama is basically an agricultural sickle, called Kama in Okinawa, with a cord attached to the end of the handle. There are a number of versions of the Kusarigama, with the biggest variation in the length of the handle and the size of the blade. Also in the larger versions, a weighted object is secured at the other end of the cord which permits the weighted end to be thrown at the opponent in an attempt to entangle him and then be able to move in for the finish. In Japan, the larger versions of the Kusarigama is the most popular, while in Okinawa the smaller versions are preferred. A noted practitioner of the "flying kama" techniques was the late Seike Toma in Okinawa.

Jo

The Jo or Hanbo (half-bo) were 4′ and 3′ variations of the Bo staff. They were often carried by the Okinawan royal court guards as it gave them an excellent weapon to use within cramped confines. A very practical weapon with a lot of modern day potential. Only a handful of kata exist which primarily come from the Taira or royal court guard traditions.

Tanbo

The Tanbo or Nitanbo were short wooden sticks most often used in pairs, measuring anywhere from 24" to almost 3 feet. The highly effective techniques, reminiscent of the Philippine arts, but simpler, see limited practice even in traditional Kobudo circles.

Kuwa

The Kuwa or wooden hoe is another minor weapon which is not often seen even in the most traditional of the kobudo schools. Probably the most noted practitioner of this weapon keeping the tradition alive was the late Shinpo Matayoshi of Okinawa.

LINEAGES OF OKINAWAN KOBUDO

As discussed earlier in this article, for most of the history of Okinawa Kobudo, its focus was to separate Kobudo Organizations apart from the Karate organizations. One of the first individuals to formally combine a traditional weapons lineage with a traditional karate style was the last Master Seikichi Odo. Master Odo taught the weapons program at Shigeru Nakamura’s dojo (his karate teachers school). Master Odo had received his kobudo training from some of the top current and past kobudo practitioners including: Kakazu, Matayoshi, Toma, Meazato, Kinjo, Kyan, Kuniyoshi and Sakiyama. Prior to the passing of Master Nakamura (the founder of the Okinawa Kenpo style) he asked Master Odo to continue to teach the kobudo program and to formally incorporate it into the karate program – thus the birth of Master Odo’s Okinawa Kenpo Karate Kobudo system in the early 1970’s. In recent years most of the major traditional karate systems now have also incorporated a program of formal weapons training.

Major lineages of traditional Okinawan Kobudo include the following:

TAIRA LINEAGE – This lineage traces its roots to Shinken Taira. Weapons taught include the bo, sai, manji sai, tunfa, kama, nunchacku, tekkos and tinbe. The majority of the Shorin-ryu, Isshi-ryu, Uechi-ryu and Japanese Kobudo trace their roots to this lineage.

MATAYOSHI LINEAGE – This lineage traces its roots to the teachings of Shinko Matayoshi. Weapons include a full range of the traditional Okinawan weapons with the addition of a number of Chinese basic weapons as well. A significant number of the Okinawan Kobudo practitioners trace all or part of their roots to this lineage.

UHUCHIKU LINEAGE – These teachings come from the famous Sai master Sanda Kanagusuku. This lineage teaches the sai, kai, tunfa, nunchaku, kama, tekkos and bo.

ODO LINEAGE – This is a more modern lineage coming from the teachings of Seikichi Odo and his Okinawa Kenop Karate Kobudo system. The weapons taught include the bo, sai, tunfa, nunchaku, kama, tekkos, eiku, nunte bo, yari bo, tinbe and rochin. This is also the lineage of the author of this article who was a senior student of the late Master Odo.

MOTOBU LINEAGE – These teachings come from the late Seikichi Uehara also was also noted for his teaching of the Okinawan Folk dances. The weapons taught include: katana, naginata, yari, tanto, bo, jo, tunfa, eiku and sai.

CHINEN LINEAGE – This lineage also referred to as “Yamani-ryu” traces their roots back to Sanda Chinen. The system was primarily a bo system, and the katas worked are worked by many of the Shorin-ryu and Goju-ryu practioners today.

KUNIYOSHI LINEAGE – This lineage also referred to as “Honshin-ryu” traces its roots back to Shinkichi Kuniyoshi, a famous weapons master. Weapons taught include the bo, sai, tunfa, and kama.

OVERVIEW OF TECHNICAL PRINCIPLES

One of the most important technical principles involved in the practice of Okinawan Kobudo is the "removal of target". By this we mean that the defender uses body positioning to cut an angle either defensively or offensively to the opponent, thus minimizing their vulnerability and maxamizing their offensive capability. In order to accomplish this, the defender must be able to adjust his stancing and movements to reflect and enhance the technical capabilities unique to each weapon.

A second important principle deals with the "control of centerline". Just as with the open hand arts, the individual who effectively controls the centerline has the greatest chance for success. Here again, stance adjustment is critical for the defender to maintain his/her control of the centerline – which lead one noted Kobudo Master (the late Seikichi Odo) to state that …"there are no stances in kobudo". Thus, while many martial artists commonly refer to Kobudo as …"being an extension of your Karate technique", it must be recognized that the "extension" is not one of basic Karate technique, but according to the author …"rather the enhancement of the underlying principles".

The difference in stancing between karate and kobudo is a very important distinction which is not readily recognized my most martial arts practitioners. One can not just take their standard karate (open hand) stances and techniques, add a weapon(s) and have “functioning kobudo”. Stancing is only a foundation for the weapons being used by the martial artist whether they are their open hands or their weapons. No one has ever won a fight solely based upon their stances, but many have lost a fight due to poor stancing resulting in lack of balance, power, etc. With the practice of Kobudo the stancing adjusts to the length of the weapon. With the long weapons such as the bo, nunte bo, yari, etc. the stancing is long and narrow permitting the end of the particular weapon to be able to control the centerline in a relaxed natural manner. With the intermediate range weapons such as the nunchaku, sai, tunfa and kama the stancing is still not as wide as ones normal karate stance (shoulder width). It is only with the short range weapons such as the tekkos, that the stancing approaches that used for ones open hand techniques.

The practice of traditional Okinawan Kobudo involves more than just performing a series of kata (forms). Like standard Karate practice, Kobudo practice also involves basic drills, bunkai (applications), disarms, throws, joint locking techniques and weapons sparring (fighting). In order to provide a level of safety for the practitioners, weapons fighting is performed with full body protective equipment in order to minimize the risk of injury. In addition, there are modifications made to the weapons to further promote safety such as taping over sharp weapons such as the blades of the kamas, or padding metal weapons such as the sai. The last and just as important part of Kobudo practice is learning how to defend against an opponent who has a weapon when you are unarmed. In order to use a weapons to its fullest as well as to be able to defend against a weapon, the student needs to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the weapon.

* * *

Hanshi Heilman, through his Heilman Karate Academy and International Karate Kobudo Federation (IKKF) is dedicated to the propagation of traditional Karate and Kobudo in order that the old ways will not be lost to the future generations of students. This article is just another step in the process of getting the history, techniques and principles of the "old ways" out to the serious martial arts public.

Thanks to Hanshi Heilman for participating in this exciting month of Admired Martial Artists. For more information on the schedule for the month, go here.

Admired Martial Artists Month is HERE!

It’s finally here! Each Monday, during the month of March, another exciting martial artist will grace the BBM blog with their presence. For more information about the contributors, go here. Enjoy! I know I will! Please scroll down for new entries.

To make this month even more exciting, The BBM Review in conjunction with Turtle Press, will be giving away six martial arts prizes this month. For more details, visit The BBM Review! The last chance to enter the contest is on Friday, April 4th by noon Eastern time. Leave a comment and get entered to win! The drawing will take place Friday evening and the winners will be announced on The BBM Review.